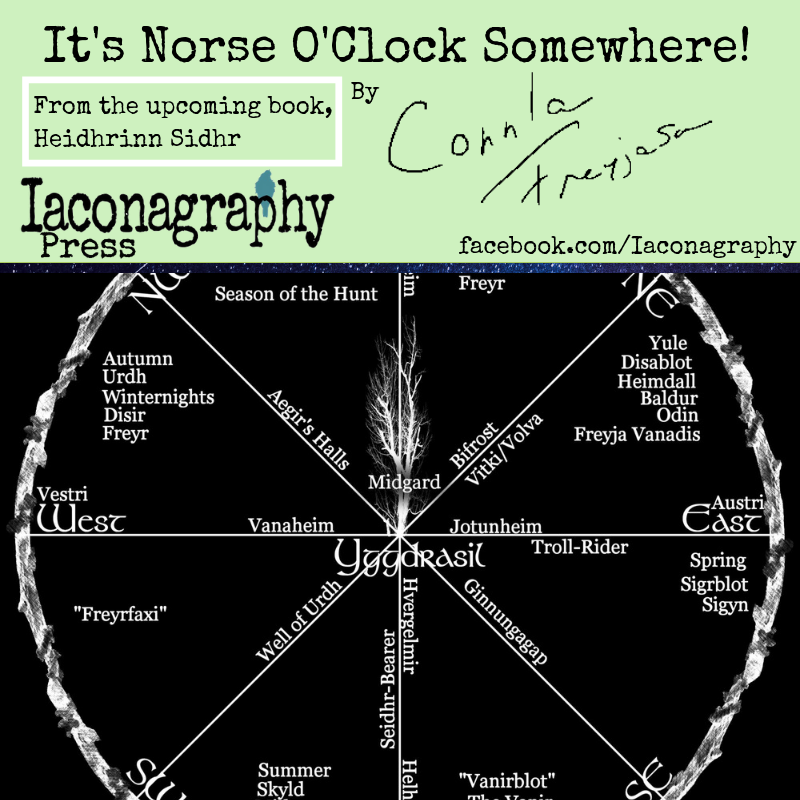

It’s Norse O’Clock Somewhere!

I have personally discovered that one of the most frequently argued topics, among American Heathens, is the Wheel of the Year, and whether we have one or not. When you say those four words to someone—Wheel of the Year—often their minds will immediately wander to the Wiccan or Druidic Wheel of the Year, popularized by Gerald Gardner and Ross Nichols, respectively. Consequently, some will look at this Wheel, as I have presented it in my book Blessings of Fire and Ice, practice it in my own life, and feature it likewise in future books, and balk immediately. You see, the Wiccan and Druidic Wheel of the Year, though based in part in ancient traditions of the Celts and others, is anything but entirely ancient. The fact remains, however, that the agricultural cycle is precisely that: cyclical. So is the entire Norse concept of time on the whole. Cycles, my dear friends, are circles, and guess what? So are wheels!

The Wheel that I present in my books and that I practice in my life is based as closely as possible on concrete historical evidence, drawn not only from Lore, but also the archaeological record, folkloric and ethnographic evidence. In the Lore itself, we find listed three requisite blot feasts:

“Þá skyldi blóta í móti vetri til árs, en at miðjum vetri blóta til gróðrar, hit þriðja at sumri, þat var sigrblót.”

“There should be a blot at the beginning of winter for a [good] year, and at mid-winter a blot for growth, the third at summer, that was Sigrblot [“victory blot”].”

—Ynglingatal, my own translation

Here we have Winternights, Yule, and Sigrblot. We can deduce that the beginning of winter basically occurred in Uppland Sweden at a point near the Autumn Equinox (mid-September), giving us a date for the observance of Winternights. The point of mid-winter is known to us today as the Winter Solstice (mid-December), at which time we celebrate Yule. Finally, from this we learn that Sigrblot, a blot for victory (celebrating the successes of life), was observed at the beginning of summer. We can deduce based on a basic understanding of weather patterns in Uppland Sweden that the beginning of summer (from an agricultural standpoint) coincides roughly with the beginning of Spring, which we recognize today as the Spring or Vernal Equinox (mid-March).

Another lore-based holiday is Alfablot. Apparently largely specific to Sweden (according to the account in Austrfararvisur), it consists of offerings to the Alfar (not only Elves in the traditional Norse sense, but also male Ancestors; please see my chapter on the Alfar in Norse Witch: Reclaiming the Heidhrinn Heart). Alfablot was apparently a very private observance within the home, and there is evidence (particularly from the aforementioned text) that during this “season” people closed their doors to outsiders and did not offer them the usual requisite hospitality. This is likely due to a belief that it marked a time of year when the “veils were thin”, implying that not only anyone but essentially anything might “come knocking” on a household’s door, therefore demanding caution and precautions. This holiday was most likely celebrated in the late autumn, likely on or around the same time as the modern Halloween or Samhain, and with similar spiritual and cultural motifs of Ancestor veneration and respect for and celebration of the Beloved or Revered Dead.

Recent studies of the sunsets and sunrises over the Thing Mound at Gamla Uppsala have not only revealed the ancient mound’s status as an intentionally aligned astronomical feature, but also confirmed Yule as a season, rather than simply a feast day. The sunset on November 8 each year is the “kickoff” of the Yule Season. Other sunsets and sunrises over the mound include that of February 3, which coincides with Disablot (also mentioned in Lore), and the sunrise on April 29, which is a date not dissimilar from that of Beltaine in the traditional Pagan calendar.

That date—April 29—becomes even more interesting when one considers the finds at the confirmed Iron Age festival site of Hulje, Sweden. Finds in the well there have been dated to a time roughly concurrent with May Day, and include offerings to both Freyja and Freyr, both of whom are obviously fertility deities. This confirms that, at least in ancient Sweden, the Ancestors definitely celebrated something similar to the modern traditions of May Day. I have dubbed this holiday “Vanirblot”, as that is the most logical thing to call it. Without benefit of written records from the time period, the best we can do is develop a name based on the archaeological evidence.

The site at Hulje also provides us with valuable information regarding two potential summer holidays, at Midsummer and later, approximately near the beginning of August. Midsummer, of course, is still widely celebrated throughout Scandinavia at the time of the Summer Solstice (mid-June), providing us with vast amounts of folkloric and ethnographic evidence. The other holiday suggested by finds at Hulje, which I have chosen to dub “Freyrfaxi”, would likely have fallen during the same period as Lammas, and had similar associations of harvest, particularly as it pertains to grain. Why “Freyrfaxi”? Because the finds at Hulje involve evidence of horse fighting, racing, and sacrifice.

In our modern global community, many who live in the Southern Hemisphere “flip” the traditional Pagan Wheel of the Year to suit their resident climate. Midsummer, rather than being celebrated in June, when it is actually winter in the Southern Hemisphere, is instead observed in December, for example. The argument is generally made that because the Wheel of the Year is actually a solar and agricultural calendar, it “makes more sense” to celebrate Midsummer when it is actually summer in a region, rather than in the dead of winter.

The Wheel of Ice and Fire which history upholds for those practicing within a Norse paradigm is not the same as the traditional Pagan Wheel of the Year, even though, as (remotely) agricultural calendars, they definitely do have things in common. Instead of being based entirely on the agricultural cycle, it is instead based on the actual practices of the Ancestors: practices which did not wholly revolve around fertility motifs. Disablot, for example, has nothing whatsoever to do with what might be happening (or not) out in the fields; the same can be said for Alfablot, Yule, Sigrblot, and to a large extent, Midsummer. The Ancestors observed these days within the context of not only a particular culture, but also a particular climate and a very specific understanding of how time flows. Which has led me to coin the phrase: “It’s Norse o’clock somewhere”.

The idea of “Norse o’clock” represents a very specific and distinct understanding of the flow of time, in which the past, the present, and the future are neither mutually exclusive, nor entirely linear. In The Well and The Tree: World and Time in Early Germanic Culture, Paul Bauschatz explains this understanding of time in this way:

“[Wyrd] governs the working out of the past into the present (or, more accurately, the working in of the present into the past).”

According to that understanding of time (and, indeed, as observed in the mundane world), simply because it is winter where you live, does not mean it isn’t spring somewhere else. This “Norse o’clock” concept also means that just as we are attempting to work the past into the present, through the revival of this ancient faith, we are also, without even realizing it, working our present into the past of the Ancestors. In short this means that we are not as far removed from them as most of us tend to think. It also means that as we are observing these days in the present, we are doing so not only at the same time as the Ancestors, but also alongside them. Because of this “Norse o’clock” understanding, we do not “flip the wheel” for the Southern Hemisphere in Heidhrinn Sidhr. After all: the timing of the sunsets and sunrises over the Thing Mound at Gamla Uppsala do not change, simply because a modern practitioner happens to live in New Zealand. So, yes, “it’s Norse o’clock somewhere”.

In the time of the Ancestors (of Kith, Kin, and Path), this “Norse faith” was neither homogeneous nor fundamentalist, and any attempts by us, here in the modern world, to make it either of those two things is a profound disservice to them. “My” Wheel may not speak to you or work for you, and that’s perfectly okay, but it does work for me, and it works for me precisely because it is sourced from real historical sources within Uppland Sweden. Too much of modern practice is not sourced at all from genuine Iron Age historical sources, but instead from a much later period: the mysticism of Third Reich-era Germany, as regurgitated by the minds of the founders of American Heathenry in the 1970s. What happens when the point in the past from which we are working is actually a later point in time, as has been the case in American Heathenry since its birth in the 1970s? Given the source of that “history”–Third Reich-era Germany, remember–all of the ugliness that went along with that regime has steadily been worked and woven into the present, which effectively also works the present into the past, creating a perpetual circle of hate. This means that the racism of that period is being worked into the present, as well as the “evil-skepticism” which helps such ideals to survive. Look around, then I dare you to come back and tell me that I’m wrong. Now, what if we, instead, actually worked from the actual period in which the Ancestors genuinely lived and practiced? This would mean that we would be working such things as concepts of animism and interconnectedness into the present, as well as themes of hospitality and reciprocity, while at the same time actually repaying gift-for-gift with our Ancestors. Instead of promoting attitudes of exclusion, we would adopt and adapt, as did the Ancestors, creating new cycles of exploration and understanding, wherein the Gods are alive and wild.

So I invite you to set your spiritual clock to “Norse o’clock”, remembering that then is now, and now is then. If Uppland Sweden is not the place to which you feel your heart calling you back and back and back, do your homework: do your own research into the archaeology and living history of the place that your heart calls home. Use that to find the way to your own Wheel. And then walk it, every day in every way, embracing and celebrating not only with the Ancestors, but also the Gods and the Invisible Population.

Shine on!

(Featured in Connla Freyjason’s upcoming book: Heidhrinn Sidhr, from Iaconagraphy Press)

Bibliography

Bauschatz, Paul C., The Well and The Tree: World and Time in Early Germanic Culture. Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press, 1982.

Freyjason, Connla. Norse Witch: Reclaiming the Heidhrinn Heart. Iaconagraphy Press, 2018.

Henriksson, Goran. “The Pagan Great Midwinter Sacrifice and the ‘Royal’ Mounds at Old Uppsala.” Calendars, Symbols, and Orientations: Legacies of Astronomy in Culture, Proceedings of the 9th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Astronomy in Culture (SEAC), Blomberg, M., Blomberg, P., & Henriksson, G. (eds.), Uppsala, Sweden, 2013, p. 15.

Petersson, Maria. “Hulje: Calendrical Rites Along a Small Stream”. Electronic Journal of Folklore volume 55, pp. 11-48, 2013.

Zakroff, Laura Tempest. Weave the Liminal. Llewellyn Publications, 2019