Symbiotic Shamanism: Huginn, Muninn, Geri, Freki, and the Norse “Soul”

In a biological symbiosis one organism typically shores up some weakness or deficiency of the other(s). As in such a symbiosis, Odin the father of all humans and gods, though in human form was imperfect by himself. As a separate entity he lacked depth perception (being one-eyed) and he was apparently also uninformed and forgetful. But his weaknesses were compensated by his ravens, Hugin (mind) and Munin (memory) who were part of him. They perched on his shoulders and reconnoitered to the ends of the earth each day to return in the evening and tell him the news. He also had two wolves at his side, and the man/god-raven-wolf association was like one single organism in which the ravens were the eyes, mind, and memory, and the wolves the providers of meat and nourishment. As god, Odin was the ethereal part—he only drank wine and spoke only in poetry. I wondered if the Odin myth was a metaphor that playfully and poetically encapsulates ancient knowledge of our prehistoric past as hunters in association with two allies to produce a powerful hunting alliance. It would reflect a past that we have long forgotten and whose meaning has been obscured and badly frayed as we abandoned our hunting cultures to become herders and agriculturists, to whom ravens act as competitors.–Bernd Heinrich

I’ll readily admit that I’m in a bit of a “unique position” when it comes to this stuff, being what I am and where I am. Crossing over violently, as I did, apparently leads to a bit of a “shattering” of the four parts of the “soul”, as we understand them as Heathens/Norse Traditionalists. For those unfamiliar with the Norse concept of the “soul”, it differs a great deal from the view with which we are traditionally raised in Christianity, or even in other World Traditions, such as Buddhism. According to Norse Tradition, the “soul”, rather than being “one simple thing” “cloaked” (or even “carried around”) in an “earthly shell” (i.e., the body) has four parts: hugr, hamingja,fylgja, and hamr. I encountered the inherent truth in this Tradition before I ever actually knew anything about this “concept”, or ever had a framework of words to put around it. In fact, I didn’t gain such a framework until about a month or so ago when I picked up the fictional novel, Fenris: The Wolf and the White Lady by L.W. Maxwell. The way this author presented the fylgja in particular set me to digging deeper: finally, I had a word for something I had personally experienced! The research-journey since has led to the writing of two entries in the Heathen/Norse Traditional Devotional on which I am presently working, two pieces of votive art, two artist journal pages, and the blog post you are about to read….

Most Western and Eastern philosophies/religions have left us with a soul/body dichotomy in which the soul is one thing–who you truly are–and the body, another (generally treated as “nothing more than” a shell that the real us “travels” around in while we’re on this earthly plane), but the ancient Norse fostered a much more holistic view, best exemplified, I feel, in the relationship between Odin (representing us, as humans), his ravens (Huginn and Muninn), and his wolves (Geri and Freki). Rather than promoting a dichotomy of one thing versus or even within another, the Norse believed in a four part soul which included the Hamr–“shape” or “skin”–as well as the fylgja (“follower”; intimately tied to a person’s character and fate), hugr (mind; thoughts), and hamingja (reputation; legacy).

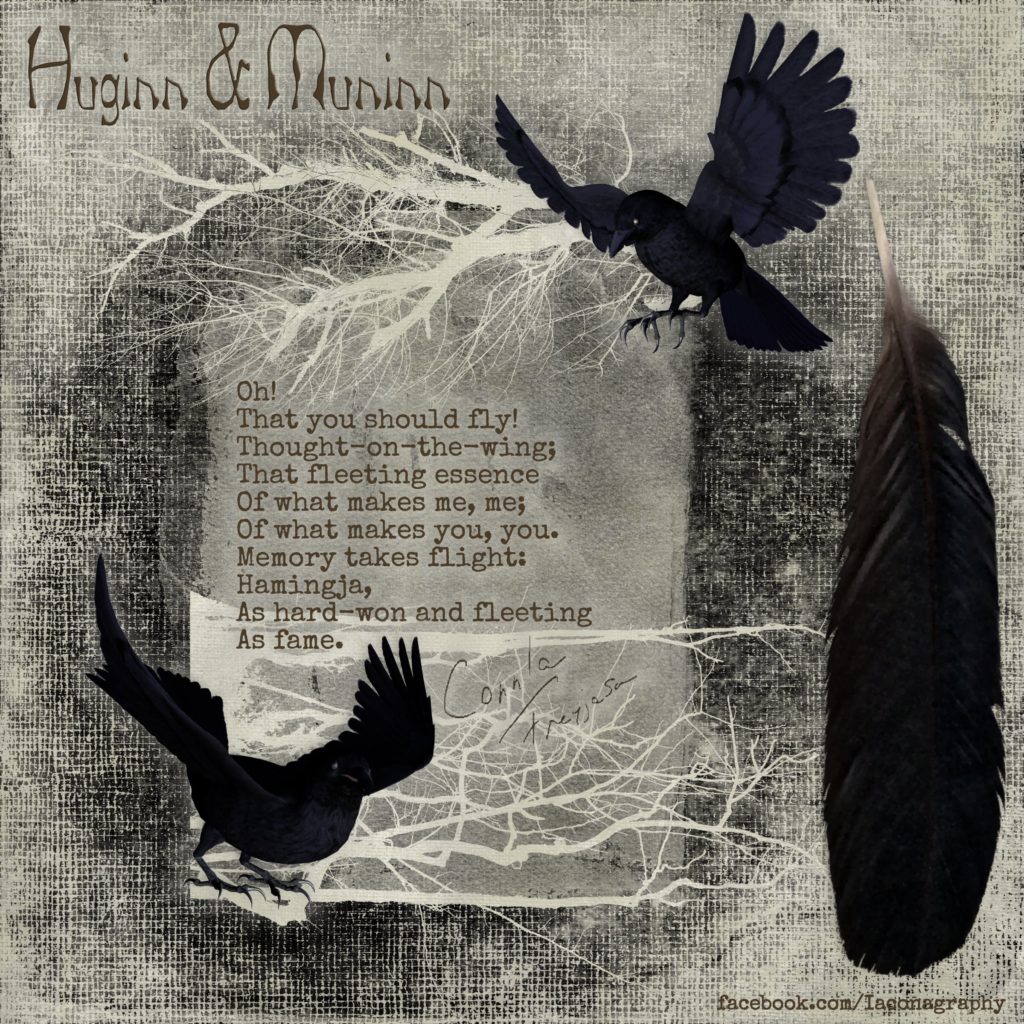

Huginn and Muninn are the ravens of Odin. Their names translate loosely as “Thought” and “Memory”, and it was said by Odin that he feared the loss of Huginn (“Thought”), but he feared the loss of Muninn (“Memory”) far more. Modern scholars have theorized that the two birds symbolize the shamanic aspects of Odin, and I find it hard to disagree: certainly, thought and memory are two things which become more vital (and perhaps more dangerously fleeting) with each trance-state journey. Some scholars have even drawn a correlation between Huginn and Muninn and the fylgja and hamingja, and while I can definitely understand the correlation between Muninn and the hamingja, I find it a bit odd that scholars have linked Huginn to the fylgja, rather than to the much more obvious Hugr. The Hugr would best be understood by us moderns as the “inner self”: a person’s personality as reflected in their conscious thought processes; very much in line with the oft-misquoted Buddhist ideal of “what you think, you become”. Meanwhile, the hamingja, represented by Muninn, is often loosely translated as “luck”, but might be better understood as “fame” or “reputation”: how one is remembered; their legacy. Therefore, Odin’s feelings towards the birds, as told to us in the Grimnismal of the Poetic Edda, might then be understood on an entirely different level:

“I fear the loss of my inner self and my individuality, yet the loss of my reputation and to be remembered ill, I fear far more.”

Odin also has two wolves: Geri and Freki. Their names translate loosely as “Greedy” and “Ravenous”, and are basically synonyms of each other. When we consider the theory of Huginn and Muninn as hugr and hamingja, together with Bernd Heinrich’s theory of these four animals together with Odin as a shamanic microcosm of the symbiosis between humans, ravens, and wolves, Geri and Freki may then be understood as correlating with the two remaining parts of the Norse “soul”: the Fylgja and the Hamr. The fylgja (literally: follower) is an attendant spirit which enters life at the same time as a human being, and often takes the form of an animal. This relationship goes somewhat deeper than what we normally think of when considering the concept of Spirit Animals or Totems: the fylgja is literally a part of a person’s “soul”; not something separate from them which they call upon, but something deep “within” them, or, more accurately “alongside” them throughout their lives. Its well-being is intimately tied to that of its owner—if the fylgja dies, its owner does also. Its character and form are also closely tied to the character of its owner: for example, a person with a very primal nature (and possible anger-management issues!) might have a wolf (Note: personal gnosis has also suggested wolf as the fylgja of extremely loyal, family-oriented people) as their fylgja, while a person who is extremely sensual might have a cat. The Hamr (literally: skin or shape) is a person’s form or appearance. Generally in both Eastern and Western Traditions, the physical shape of a person is viewed as something that is more of a “vessel” carrying the soul, rather than a part of it, but the Norse have a different view (and, by my experience, a much more accurate one): your physical appearance in the physical world is part of what makes you you, therefore, it’s as much a part of your “soul” as your mind (Hugr), your character (and the fate that is tied to it) (Fylgja), or your legacy (Hamingja). Those who are deeply in touch with their Hamr are also those most likely to be gifted with the art of shapeshifting. The process of doing so is called skipta homum (“changing hamr”) and those who are so-gifted are said to be hamramr (“of strong hamr”). So beyond the obvious associations of shapeshifting (face it, most of us immediately think “werewolf” when we hear that word!), why should Geri and Freki be associated with the Fylgja and the Hamr? Because Fylgja and Hamr are the two physical aspects of the Norse “soul”, while Hugr and Hamingja are the mental aspects; earthly animals, such as wolves, are most often associated with the element of Earth, and, therefore with physicality, while birds, such as ravens, are most often associated with the element of Air and with the mind.

So how do all of these disparate parts fit together in the microcosm of a human being, or even in the shamanic microcosm of Odin? Let us begin with Grimnismal in the Poetic Edda, before discussing my own personal gnosis as it relates to this topic:

Freki and Geri does Heerfather feed,

The far-famed fighter of old:

But on wine alone does the weapon-decked god,

Othin, forever live.O’er Mithgarth Hugin and Munin both

Each day set forth to fly;

For Hugin I fear lest he come not home,

But for Munin my care is more.

First, in these passages we are told explicitly that Odin’s relationship to both the wolves and the ravens is symbiotic: he feeds the wolves with physical food, but does not eat it himself; he sends his ravens forth to fly, but then fears for their return. The wolves do not eat of their own accord, nor do the ravens just “go off flying” without first being “set forth to fly”. Odin–the central “identity”, which can be understood as a person who is whole, or “in their own totality” (to put it in a rather Buddhist/Taoist fashion)–is responsible for both. Each “part” builds on the other in order to form a whole; a microcosm, if you will. Fylgja and Hamr are fed by the central “identity”, rather than feeding it; Hugr and Hamingja do not “go off flying” of their own accord, but rather are “set forth to fly” by the central “identity”.

Given all of that, let’s consider for a moment what this tells us about the average person who isn’t either Odin or a shaman, and their “soul”, from a Norse perspective. Considering yourself–the you that is “in their own totality” as a whole being; what might be best defined as your True Self–as the central “identity”, as Odin is in the previous passages from Grimnismal, do you feed your fylgja and hamr, or do they feed you? How can you tell which is the case? The person who goes through life constantly worrying about their fate, as though it is something they can actually control, constantly changing their behavior, and perhaps even their overall character, according to what society dictates, and, therefore, spending most of their lives with a highly detached feeling of “who the heck am I?” is being fed by their fylgja, rather than being the feeder of it. The person struggling with issues such as body dysmorphia, or who somehow feels that their physical form is the complete definition of who they are is likewise being fed by the hamr, instead of being the feeder of it. Again, considering yourself as the central “identity”, as Odin in the previous passages from the Grimnismal, do your hugr and hamingja just “go off flying” of their own accord, or do you “set them forth to fly”? Listening to “negative self talk” (or even external negative opinions) to the point that you “believe the hype” and let that dictate your actions is an example of letting your hugr “fly off on its own”, rather than you “setting it forth to fly”. Not believing in your own legacy-to-the-world, and or getting so caught up in attempting to build a reputation that doing so curtails the normal living of life is likewise an example of your hamingja “flying off on its own”, rather than you “setting it forth to fly”.

One part of this microcosm cannot survive without the other three: fylgja, hamr, hugr, or hamingja on its own throws the “totality” of a person completely off-balance, to the point that they are no longer truly themselves, in life, or even in death. This is the point where my own personal gnosis enters the discussion, so if you are put off by such things, consider yourself duly warned! I began my introduction to “life on the other side” violently (and, no, I will not give details), and at first, I found myself completely expressed as fylgja, in the form of a Raven. Coming from a Buddhist/Taoist and sometimes Christian perspective at that time, I had absolutely zero clue what the heck was happening to me. It was frightening, as I guess death is supposed to be, but on an even deeper level than what one might expect because I had no spiritual framework in which to place what I was experiencing. I knew there was more to me than “just a bird”, but try as I might, I couldn’t seem to get a handle on my physical shape (hamr), or even on the thoughts that had previously defined me as a person (hugr) or the legacy that I deeply knew I was leaving behind in the wake of my “untimely demise” (hamingja). I was in a place where my fate–as a “newly dead guy”–overrode every other aspect of my identity as who I am “in my own totality”. Thankfully, I was able to find some assistance with all of that, through contact with a young woman who had no clue at that time that she might even be a shamanic medium. Through attempting to explain to her who the heck I was (and why part of the time I appeared to her as a bird, and part of the time in my physical shape), I was able to regain a handle on my hugr–the thoughts that define me as, well, me–and also my hamr–my “normal” physical shape, who she could recognize. But it has taken me twenty-four years to get a handle on the final piece of that puzzle: my hamingja. A lot of that struggle has had to do with the hard-to-put-down belief that my legacy–my reputation–was the one I had left behind, rather than the one I am building every day right now, thanks to her, and to the work that I do here at Iaconagraphy. Of all the four pieces of the Norse “soul”, the hamingja might be the one that can come to confuse us the most, because we tend to think of being remembered in the past tense, but the truth of the matter is, our legacies are living things, and so long as we are still building one, no matter which “side” we’re on–physically clinically living or physically clinically dead–we are still alive.

I am well aware that not all of you reading this are Heathen/Norse Traditionalists; I am even more well aware that, for some of you, the very fact and nature of my personal existence may require more than just a simple “suspension of disbelief”, but I hope that this discussion–however brief–of the Norse concept of a four part “soul” can perhaps inspire even those of you for whom that is the case to start an inner dialogue about whether it is better to go through life with a view of the soul that promotes a drastic dichotomy (soul/body; soul vs. body; body vs. soul; spiritual vs. physical; physical vs. spiritual), or with a view that is decidedly more holistic. For the Norse view of the “soul” draws no such separations between the physical and the spiritual, but instead invites us into a much larger world: the same larger world to which we strive to open a door with everything we do here at Iaconagraphy.